Failure to launch: What can Blue Jays do to fix the offense?

TORONTO - The Toronto Blue Jays are struggling at the plate. That's no secret.

They entered play Thursday ranked 29th in the majors in runs scored and rank near the bottom of the majors in slugging, home runs, and an assortment of other categories.

Part of the issue is obvious. Core lineup fixtures like George Springer, Bo Bichette, and Vladimir Guerrero Jr. are failing to meet expectations to varying degrees, and the club purposefully became more defensive-minded in recent seasons within its position-player group.

Moreover, despite courting Shohei Ohtani, no star-level external additions were made in the offseason. Any offensive improvement this season was going to have to come internally, from a team that fell from third in runs scored in 2021, to fourth in 2022, to 14th last year.

But that internal improvement has yet to happen on a large scale, and this trend must change if the Blue Jays are to turn things around in the competitive A.L. East.

Can that happen?

Looking further under the hood, there are more troubling indicators. In the new bat-speed metrics released to the public by MLB this week, the Blue Jays rank last in the majors in average bat speed, one spot below the lowly Chicago White Sox. That matters because bat speed is a critical performance driver. It's also a skill that is difficult to change.

Individually, 10 of the 14 Blue Jays who have at least 10 measured swings are below the MLB average of 71.3 mph. Cavan Biggio (65.3 mph), Justin Turner (65.4), Ernie Clement (66.4), and Isiah Kiner-Falefa (67.3) are among the slowest bats in the league, all ranking bottom 35 among the 384 hitters to have taken at least 50 swings through play Monday.

Bichette (70.5 mph) is also below the average, although Guerrero (75.5) and Dalton Varsho (72.3) are above.

The team is unlikely to make any meaningful improvement in hitting the ball harder this season unless there's an extreme and unlikely makeover of the roster.

The Blue Jays also rank in the lower third - 24th in the majors - in another key underlying offensive category: percentage of batted balls pulled in the air.

Presented with that ranking recently, the Blue Jays' Justin Turner had a straightforward answer: "Not good."

A pulled ball in the air is the most valuable batted-ball type in the majors. The fences are closer down the lines, and the pull side is typically where a batter features his top power.

For instance, MLB batters are enjoying an OPS of 1.739 on pulled balls hit in the air to the pull side this season.

To the opposite field? Only .688.

The Blue Jays are not hitting to the pull side often enough, which Turner describes as a "shortcut" to productivity. And unlike bat speed or exit velocity, this is an area where the club can improve.

Bichette and Guerrero, the cornerstones of the Jays' offense, are not tapping into this power. Out of the 350 batters to put at least 20 balls in play through Wednesday, Bichette ranks 336th in the percentage of balls hit in the air to the pull side (13.3%), while Guerrero ranks 286th (21%) and Springer ranks 275th (22%).

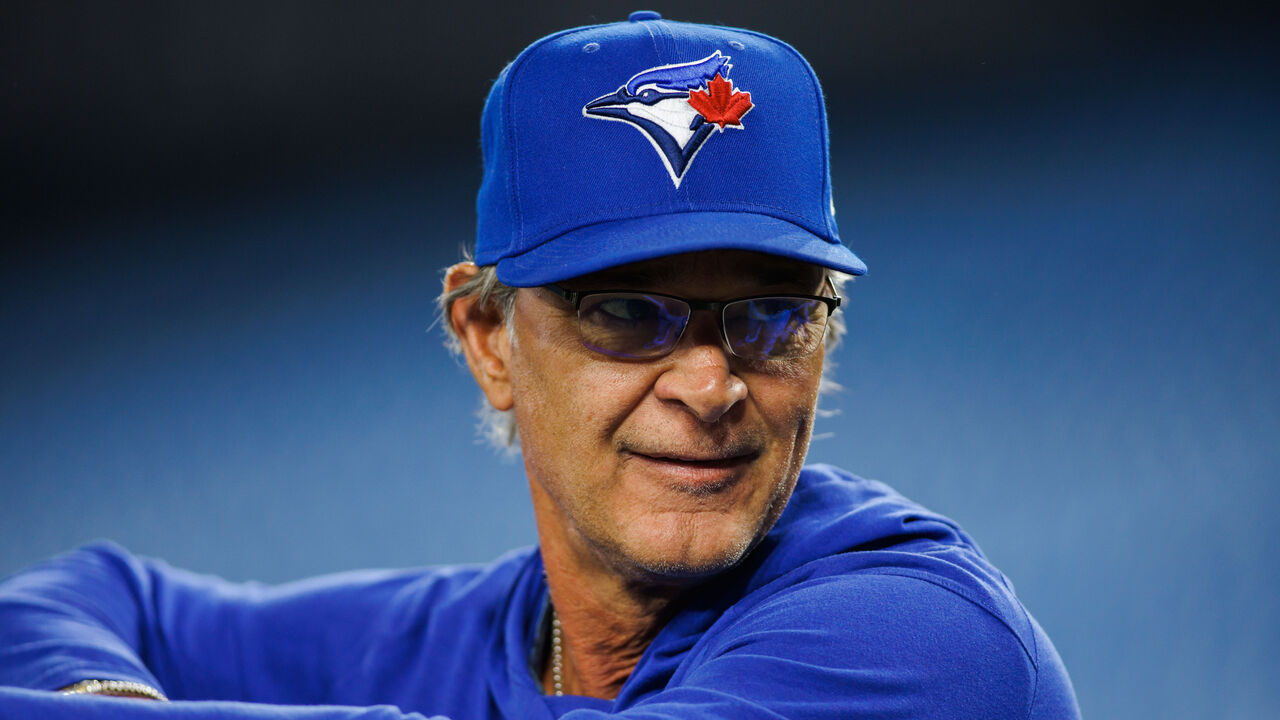

Blue Jays offensive coordinator Don Mattingly believes power, specifically pull power, develops over time. That's what happened in his career. He debuted in the majors as an all-fields hitter and learned to become better at identifying and waiting on pitches he could drive. He became one of the game's best hitters when he started pulling balls into the right-field seats at Yankee Stadium.

"It kind of starts (with contact ability), and then progressing to learn how to pull the ball more, and understanding pitchers," Mattingly said. "In general, we are looking for guys to know themselves, and understand where they are best, and working to get balls in that area (of the strike zone). What the pitcher's mix is, what his movement is and, 'How do I get him to do what I want him to do.'"

Mattingly believes it's difficult to speed up that learning process and that a focus on pulling the ball is not suited for every player.

"You talk about the Orioles and Dodgers, they have players who have profiles to get the ball in the air," Mattingly said of two teams adept at launching balls to their pull sides. "They've brought in some hitters who get the ball in the air. … You cannot ask (Isiah) Kiner-Falefa to just pull everything in the air."

To that point, some of the Blue Jays are getting the most out of balls they put in play, like Davis Schneider and Varsho, who have hit this way for years.

"When I was a kid, I always pulled the ball in the air," Schneider said. "I never tried to go the other way. Just because I like hitting home runs, and being small in stature, going the other way, it's going to be tough to (hit home runs).

"I still work on it in practice, but it's more of a natural swing."

While time might lead to batted-ball changes, some of Toronto's core players have been trending the wrong way in recent years. Mattingly said part of the challenge in asking a player like Bichette to change is that he owes a lot of his past success to hitting the ball the other way.

"He's such a good hitter, you hate to take things away or push too fast," Mattingly said. "His foundation has been right-center, right field, and center field. That is his foundation.

"Bo is a good hitter first, and the power comes from hitting balls cleanly and getting more balls in the air. … As he gets older, and continues to mature as a hitter, you're going to see a 30-home-run guy."

Bichette was nearly a 30-homer hitter in 2021, when he hit 29. That's also when his pulled air-ball rate was at a career high.

He pulled 22.5% of his air balls that season. His rate fell to 21.1% in 2022, 19.5% last year, and a career-low level early this season.

For his career, 50 of his 91 home runs have come to his pull side. Bichette declined to talk about his hitting philosophy when approached in the clubhouse during the Twins series.

Guerrero, meanwhile, is also at a career-low pull rate.

While he's stinging baseballs with an average exit velocity of 94 mph, those batted balls are too often hit into the Rogers Centre turf or lined to center field, the deepest part of the ballpark. He's on pace for 15 homers.

The same is true for Springer, whose rate is falling for a third consecutive year. Springer is perhaps showing signs of age-related decline.

If a player was interested in making a swing change, such adjustments would ideally happen in the offseason.

But player development can happen in-season, too. Consider Turner's story.

It was late 2013 with the New York Mets when the then-light-hitting, glove-first Turner was worried about being designated for assignment following the season. In the clubhouse and on charter flights, he started listening to teammate Marlon Byrd talk about a new hitting philosophy - trying to catch the ball in front of the plate and launch balls into the air. Byrd had transformed from a ground-ball to fly-ball hitter overnight.

So one day late in the season, on Sept. 6, 2013, Turner tried to mimic Byrd. He took a big leg kick to create more energy moving forward and thought about trying to hit the ball earlier, out in front of the plate.

After grounding out twice in his first two at-bats that night, Turner launched a fastball off Cleveland reliever Cody Allen over the center-field fence. It was his first homer of the season and the seventh of his career in almost 900 plate appearances. He homered again two days later. The Mets ultimately released him, but Turner's change allowed him to transform into a star with the Dodgers. He hit 156 homers with a 133 OPS+ in nine seasons with L.A.

Turner was known for being an additional hitting coach with the Dodgers, helping players maximize their abilities. He even had competitions with former teammate Cody Bellinger to try and focus on getting the ball in the air. During his time with the Dodgers, the club's fly-ball percentage rose about 10 percentage points to 41.2%.

Turner believes more hitters should access that "shortcut" to power if they can.

"I talk about it all the time … about what I believe the principles are of hitting," Turner said. "I'm not telling anyone they should hit like me. I don't think anyone should hit like me. Hit like you, but figure out how to address all the principles within your swing. The timing. The vision. The (pitch) recognition. The decision-making. But the (bat) path has to be your own."

Turner's influence hasn't shown up in the numbers yet. The Blue Jays' overall flyball rate is down 1.2 points to 36.5% this year, while the team's pull rate is down 2.3 points to 37.7%.

There are some things the Jays cannot change this season in an effort to score more runs. It's difficult to improve bat speed. Major changes to the roster seem unlikely. Even if they call upon prospect Orelvis Martinez, one player can only do so much.

But perhaps the Jays should start listening to Turner. They need to find some way to improve offensive efficiency, and one thing they are not taking advantage of as a group is the game's shortcut to power.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.