The dream that won't die: Will a new alternative football league ever last?

Editor's note: This article was published in January 2020, before the coronavirus pandemic led to the cancelation of the XFL season.

As a football player agent, Frank Murtha never liked Labor Day weekend, because he could never let himself relax. His routine for the holiday was strict: He'd sit by his phone and hope it wouldn't ring. "But invariably," he said, "it did," with word that a client - like hundreds of other former college standouts turned NFL rookies - had been released from the only league in the United States that mattered.

Time has blurred some details of one particular episode, but the outline of the encounter evinces the stress of cutdown day. The setting: a college dormitory near the site of a 1990s NFL training camp. The team's designated "Turk" made his grim rounds, instructing late roster casualties to go meet with the coach, playbook in hand. One ill-fated player didn't answer the door. He was lying under his bed, having invested his faith in seemingly unassailable advice from his roommate: If they can't find you, they can't cut you.

"His intel was bad," Murtha recalled with a chuckle recently.

That Murtha can laugh about the gambit is a luxury of recounting it a few decades later. Eventually, the sting of even a crushing disappointment fades. Yet he doesn't invoke the memory merely for humor's sake. These days, Murtha is gearing up to offer that powerless player's successors something he couldn't so many Labor Days ago: assurance that their professional ambitions won't sputter out underneath a twin mattress.

"We can say, 'Hey, come on out from under there!'" Murtha said. "We've got a job for you."

In the only Big Four sport devoid of a professional minor-league system, players the NFL deemed expendable have at times been able to rely on a fallback option that doesn't entail heading to the Canadian Football League: the profusion of Americans who are determined to create a sustainable secondary football league.

None of these dreamers have succeeded in the Super Bowl era. Left to show for their efforts are the husks of failed ventures from the United States Football League of the mid-1980s - undone by team owner Donald J. Trump's push to compete head to head with the NFL's fall schedule - to the short-lived Alliance of American Football, whose spectacular flameout after eight weeks of action last spring culminated in a bankruptcy filing and multiple lawsuits.

The logic behind these schemes holds that if pro football is the almighty king of American sports, there must be a segment of fans clamoring to watch games when the NFL is idle. In attempting to satiate this appetite, no startup entity has managed to prove beyond reproach that sufficient demand for spring or summer football actually exists in the U.S., but that hasn't dissuaded four new sets of would-be league executives from betting that they'll be the ones to buck the trend.

You've probably heard of XFL 2.0, the $500-million reboot of the rebellious spring circuit helmed by pro wrestling mogul Vince McMahon. The original XFL folded in 2001 after one blunderous, money-burning season. Nearly 20 years later, McMahon is financing a less gimmicky offshoot whose schedule is set to kick off the weekend following the Super Bowl in eight NFL cities.

The XFL season culminates with a championship game in late April, at which point Ricky Williams, the former All-Pro running back, has signaled his intent to fill the next stretch of the NFL offseason void. Williams, Terrell Owens, and Simeon Rice are among the dozens of retired NFLers backing the 10-team Freedom Football League, which hopes to set itself apart by empowering players to participate in team ownership and encouraging them to speak out in support of social justice causes.

Pacific Pro Football is a planned developmental summer league conceived by Tom Brady's agent Don Yee. The idea is to base four teams in Southern California and stock them with top-tier college-aged talent - players who could be paid as they audition for the NFL draft rather than toiling without compensation for at least three seasons in the NCAA.

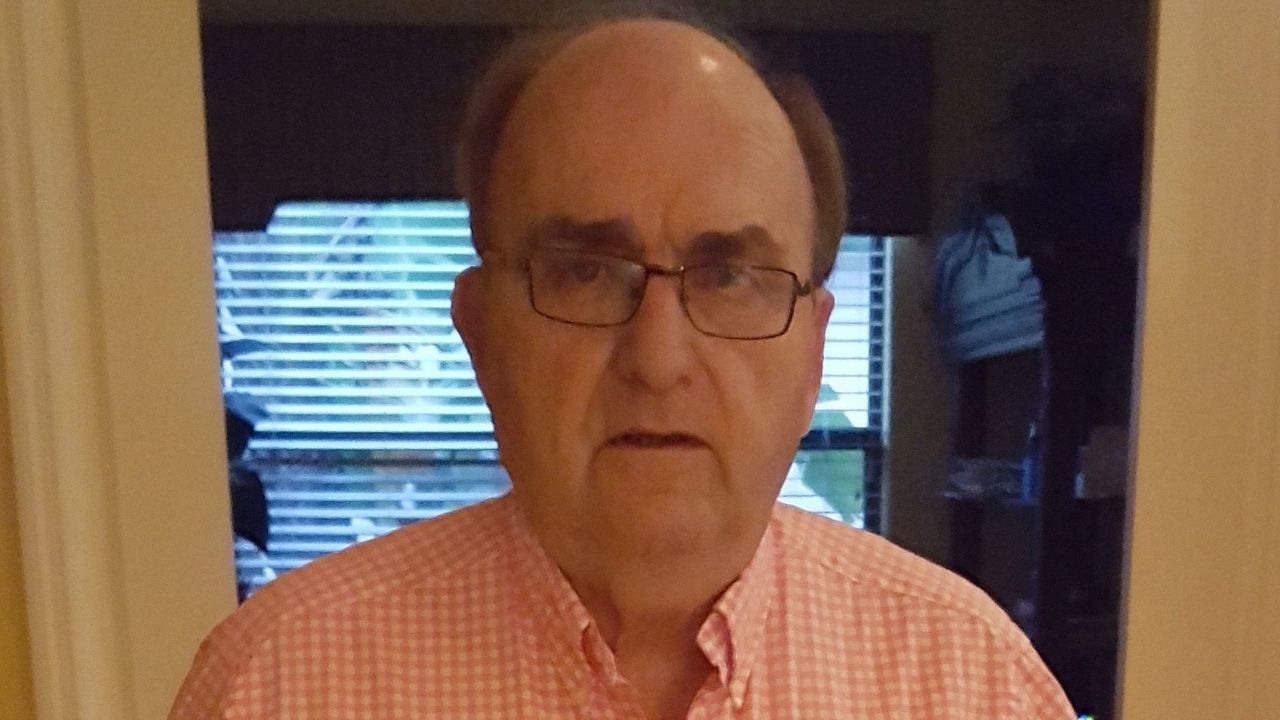

Then there's Murtha, 70, the president and CEO of Major League Football. Murtha bills MLFB as a developmental showcase, with games in May and June in six midsize cities - Little Rock, Arkansas; Norfolk, Virginia; Canton, Ohio; and so on - that aren't served by the NFL or, for that matter, Major League Baseball. Murtha's archetypal player will be a pro on the fringes of the NFL monolith, cast off from the 32 rosters but skilled enough, perhaps, to warrant another future look.

"The quality players are there," Murtha said. "The difference between the guy that gets cut and the guy that makes (an NFL) team, sometimes, particularly at the back end of rosters, is very fine."

There's no consensus on what kind of alternative league has the best odds to survive long term, as shown by the divergent organizing principles of the XFL, the FFL, Pac Pro, and MLFB. Where their proponents align is in the belief, espoused by Murtha, that a surplus of NFL-worthy talent is out there, unsigned and ready for a shot, and the conviction that their shared pursuit to start a league is no fool's errand, historical precedent be damned.

What has to happen for an entrepreneurial mind to win over fans, ward off hubris, balance the books, and finally launch a league that sticks? Last June, an investigation by ESPN's Seth Wickersham and Michael Rothstein into the downfall of the AAF described spring football as "a siren with a long lineage of wrecked dreams and wasted money." The story went on to quote XFL 1.0 executive Tom Veit's take on the question, expressed in conversation with AAF co-founder Charlie Ebersol: "Spring football will work when people learn not to screw it up."

When the 49ers and Chiefs meet in Super Bowl LIV on Feb. 2, the title game will double as the climax to the NFL's 100th season. The tradition of aspiring challengers trying and failing to puncture the league's monopoly - of screwing it up, as it were - is almost as old. Back in 1926, promoter C.C. Pyle established the original American Football League in response to the NFL denying his bid for an expansion franchise in New York. The hastily assembled nine-team loop drew mostly sparse crowds and disbanded after one season.

"It failed miserably, largely because (Pyle) really didn't take the serious approach that it needed," pro football historian Joe Horrigan said.

Subsequent upstart leagues found firmer footing over the next few decades, persuading the NFL to absorb a few more teams, in the case of the All-America Football Conference of the 1940s, and to agree to a full merger with the American Football League of the 1960s. That marriage prompted the creation of the Super Bowl and the dawn of the fortified NFL's modern era, during which no nascent league has stayed afloat for long.

The first to rise and very quickly fall was the World Football League (1974-75), the brainchild of American Basketball Association and World Hockey Association founder Gary Davidson. Playing mostly on Wednesday nights from July to December, the WFL was a momentarily disruptive force, signing away from the NFL high-profile stars such as Larry Csonka and Paul Warfield. Davidson's other creations hung around long enough to force partial mergers with the NBA and the NHL, but his football offering was severely underfunded, struggled at the gates in some cities, and folded during a recession.

"Of the sports ventures I've been in, it was the best one, but it had the worst timing," Davidson, 85, said in an interview.

Next came the USFL (1983-85), the first league that sought to capitalize on the NFL's long offseason. "I've never believed that Americans buy chewing gum only in the spring, make love only in the fall, go to movies only in the summer," founder David Dixon said in his pitch to prospective team owners, as related in "Football for a Buck," Jeff Pearlman's 2018 biography of the USFL. "We will play spring football. And people will watch."

For three seasons, many people did, impressed by the stature of players who picked the USFL over the NFL - Herschel Walker, Reggie White, Jim Kelly, and Steve Young among them - and enticed by on-field innovations such as the two-point convert. As running back Jairo Penaranda told Pearlman, "The USFL wasn’t as good as the NFL. But it was 10,000 times more fun." The league also hemorrhaged money and triggered its own demise when it abandoned the spring for a fall schedule at the behest of Trump, the owner of the New Jersey Generals.

"We had a great league and a great idea," Houston Gamblers owner Jerry Argovitz told Pearlman. "But then everyone let Donald Trump take over. It was our death."

The fatal flaws that consumed the WFL and the USFL - financial woes, fan disinterest, mismanagement - were harbingers of the flops to come. The sensationalism of the first XFL couldn't mask its second-rate play. Dozens of United Football League (2009-12) alumni later played in the NFL, but the fall-based league lost money in the nine figures. Viewership and attendance numbers were promising across most of the AAF, which nonetheless fell irreversibly into the red at breakneck speed.

Considered individually, there's hardly a model example in the bunch. Take them together, isolate the positives, and introduce a measure of patience and discipline? That's how Murtha, for one, thinks he can make a secondary league work.

For all that ailed the AAF and USFL, those leagues, as Murtha sees it, succeeded in demonstrating that fans in certain U.S. markets will take to spring football. Simple math killed Ebersol's experiment: AAF revenue totaled a reported $12 million against more than $100 million in expenses. Even before Trump guided the USFL into extinction, its owners spent carelessly and, in Pearlman's words, embraced a "terribly misguided" plan to expand from 12 to 18 teams after a single season, a grasp for expansion-fee proceeds that consequently thinned the league's talent pool.

"Like any business, (the key to sustaining is) controlling your costs," Murtha said. He outlined the balance that he said Major League Football will seek to strike: "On the one hand, putting together an entertaining product with good coaches and players who are well-coached, and, using an example, not paying head coaches half-a-million dollars."

Major League Football originally intended to stage its debut season in 2016, but shelved that plan after an anticipated $20-million investment fell through. Several executives later left the company. Over the last couple of years, Murtha has quietly spearheaded an attempted reset, working toward a formal launch announcement that he said he expects to make soon.

Ahead of that announcement, Murtha said MLFB's annual operating budget will be in the ballpark of $30 million, scaled far down from the capacity of, say, XFL 2.0. He said the league will position itself as totally non-adversarial to the NFL, seeking instead to provide coveted game reps to players - plus coaches, front-office staff, and officials still climbing the career ladder - who might otherwise languish in free-agent purgatory.

MLFB is a publicly traded single entity, meaning the league's shareholders will collectively own all six teams. Murtha said a centralized all-players training camp is scheduled for April in Lakewood Ranch, Florida, where the league is headquartered. Rather than hold a draft, Murtha said MLFB rosters might be allotted in a way that tries to ensure competitive balance while accounting for players' regional ties. (The Ohio team, for instance, could get dibs on Big Ten graduates under the latter consideration, a practice the AAF and USFL each employed.)

If, as Murtha says, financial restraint is paramount to survival, MLFB has already taken an unsuperstitious step in that direction. Late last year, the league acquired football and video equipment, as well as medical supplies, that used to belong to the AAF - $3 million worth of gear at a fraction of the price.

"Everything from uniforms, helmets, shoulder pads, on down to about 30 pallets of athletic tape," Murtha said. "Basically anything and everything you needed to run an eight-team league."

Until any league of that ilk - Murtha's, McMahon's, some other entrant to the genre that has yet to be concocted - exhibits prolonged signs of life, the champions of secondary football in the U.S. will face a high burden of proof to establish that their cause can actually be realized. How do you master something that everyone else keeps screwing up?

Davidson, the founder of the WFL, isn't sure it can be done. Speaking by phone from his office in Costa Mesa, California, 45 years removed from his foray into the game, he said he thinks football is on a downward trend across the country, beset by declining high-school player participation and too much other negative publicity. Timing is everything in business, he said, just as it was during the recession of the mid-'70s.

"There's always a balance to these things," Davidson said. "I think the balance today (would make it) very tough to start a football league."

Other former league executives are more optimistic. Michael Huyghue, the United Football League's first and only commissioner, maintains that the UFL was a quality concept - "What we did was prove that we had a good football product," he said in an interview - whose poor timing contributed to its shuttering. Billionaire funding wasn't sufficiently abundant right after the 2008 economic collapse. The 2011 NFL lockout was resolved in the summer, thwarting the UFL's chance to fill a TV broadcast void that September and October.

Above all, Huyghue said, a prospective league needs a sound revenue model underpinned by a fruitful TV rights agreement. And despite the NFL's predominance, he believes fall is the ideal time to play, when fans are known to want to watch football and when players just a notch below the NFL, fresh off a restful offseason, are ripe and ready to perform at a compelling level.

"People watch football Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. We thought if it would just occupy one of those days, people would still tune in," Huyghue said. "We wanted to be disruptive, not copycat. We thought that was an effective way to deliver the product. I still don't think it was a bad idea."

Former UFL chief operating officer Frank Vuono, a longtime sports marketing executive, is convinced that no league that overlaps with the NFL will last. Given that not all college teams use pro-style schemes, and that roster spots and practice time are scarce across the NFL, Vuono said a formalized feeder system would be the most viable addition to the pro ecosystem.

"I think you need to really work on an agreement with the NFL to be a developmental league, and you have to play in the spring, and you have to play in cities that don't have NFL football," Vuono said. "That's my thesis."

The first football game to be played after the Super Bowl will pit the XFL's Seattle Dragons against the DC Defenders on Saturday, Feb. 8. Next up: the Los Angeles Wildcats at the Houston Roughnecks. This latest attempt at revolution will be televised on ABC, ESPN, and FOX, to an audience that Huyghue figures has yet to tire of possible NFL alternatives.

"I think everybody's like, 'Let's watch the next rendition, and if it works, it works. If not, no harm no foul,'" Huyghue said. "I don't think there's any fear of taking an at-bat. But I think if you don't have really strong business acumen for running an entertainment product, you're going to fail."

Such is the test that Major League Football, too, will confront when its kickoff day arrives. Murtha said he welcomes the challenge, the allure of "building something from scratch" having drawn him to the dream in the first place. It's a new endeavor after his decades as an agent, during which he represented stars such as Andre Tippett and plenty of players he calls "sleepers" - comparatively unsung names who scrapped for everything they achieved on the field.

When Murtha expounds on his goal to employ the best jobless players out there, he thinks about the advice he'd pass along to rookie clients who weren't getting many NFL reps. Lack of opportunity has displaced many a solid prospect from the roster carousel, but they can at least control how hard they work in the meantime. They can hope for a break as they see their ambition through.

"Don't take a play off. You never know when the head coach might be looking at you," Murtha would say. "That might be your ticket to sticking around."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.